How to Price a CGC Blue Label Comic Book

When we were kids, pricing comic books was easy. Go to your favourite convenience store, see the price on the cover, and pay for it. The first books I ever bought were 75 cents. For kids in the 1930s through the 1950s, the price was typically 10 cents. For kids in the ‘60s, it was usually 12 cents.

Example of 75 Cent Comic Book

Today, as back issues, the prices of these old books differ dramatically. Sometimes they are worth less than the original cover price, but sometimes they can be worth more, much more. For this article, we’ll be focusing on comics that CGC has professionally graded. Because comics of little value are rarely graded by CGC, we’ll be focusing primarily on books of some value to incredible value. By the end of this article, I’ll provide tips for (relatively) precise estimates of comic book fair market value. But that’s getting ahead of ourselves.

The Fundamentals

Every collector should first have a command of pricing fundamentals. The fundamentals help collectors address a very important question: Does the price for this comic book seem reasonable? Those who jump straight to advanced pricing tools—without mastering the fundamentals—expose themselves to costly errors. Let’s dive in.

The first fundamental is demand, which can be influenced by several factors. Here are a few:

The debut of a major character. The bigger the character, the bigger the collector energy. For example, the first appearances of A-list characters like Batman, Hulk, and Deadpool are practically nuclear. The next tier down might include big names like Dr. Strange, Ant-Man, and Captain Marvel—still big stars, but not of the same magnitude. You can imagine lower and lower tiers until you get to characters that are some combination of obscure, uninteresting, and forgotten. Consequently, these heroes evoke virtually zero collector energy.

First Appearances of A-List Characters Attracting Huge Demand

The first issue of a major series can also drive demand, even if it isn’t a character’s first appearance. Batman #1, Wonder Woman #1, and Amazing Spider-Man #1 all fall into this category.

Big First Issues That Aren’t First Appearances

Somewhere in the mix is historical significance. For example, Famous Funnies #1 is the first comic book ever sold at the newsstand.

Historically Important Issue

Great covers capture the hearts of many collectors. In fact, some are even considered classics, such as Detective Comics #31 or Superman #14. A beloved character with an eye-popping cover—it’s easy to see the appeal. Sometimes a cover is so great, it doesn’t need a well-known superhero to grab attention. Startling Comics #49 or Punch Comics #12, for instance.

Classic Covers Featuring Superheroes

Classic Covers Without Superheroes

Let me provide some nuance: Many of the biggest books in the hobby contain several of these elements, and the collector energy intensifies.

Action Comics #1 not only features the first appearance of Superman, but is the book that introduces superheroes in general, and is often credited with launching the Golden Age of comic books. In other words, it’s the most historically significant issue in the hobby. Another example is Captain America Comics #1, which introduces Cap and features, arguably, the most well-known WWII cover.

Examples of Comics Containing Several Desirable Elements

On the other hand, a book’s demand can be hurt if it lacks an expected element. For example, most collectors hope for the hero to be on the cover of their first appearance, but that’s not always the case. More Fun Comics #73 (Aquaman and Green Arrow) and All-Star Comics #8 (Wonder Woman) feature big first appearances, but the ledes are buried in the interiors. By the way, these books still generate substantial demand, but considerably less than if the stars were featured on their respective covers.

Examples of Notable Books Lacking Expected Elements

I can hear some of you saying: “How about books that aren’t first appearances or aren’t issue #1? Can’t they also spark demand?”

Absolutely. However, it’s usually a case of diminishing returns. The 2nd appearance will be less desirable than the 1st appearance. The 3rd appearance will be less desirable than the 2nd appearance, and so forth. The same reasoning applies to the number of an issue. The first issue is typically most in demand, followed by the second issue, and so on. Be warned that the drop-off in value is usually quite steep between the first and second appearances, and between the first and second issues.

Let’s take a look at Avengers #1 through #3. As a rough gauge of demand, we’ll look at the prices of each of these books in CGC 6.0.

Price Drop from Issue 1 to Issue 2 to Issue 3

Did you notice that drop-off in demand from #1 to #2, and from #2 to #3? We would expect this downward trend to continue. But something unusual happens with the 4th issue. Demand spikes again. Why? It’s because it features the first appearance of Cap in the Silver Age! In other words, this issue is more than a mere 4th issue of a series—it generates its own collector energy based on something special.

Sometimes Later Issues Generate Their Own Demand

My final point on demand is this: it can change over time. Sometimes characters prominent in one era fade in later eras. For example, Single Series #20 was one of the most valuable books in the hobby at one time. Tarzan’s star has faded since the ‘60s and ‘70s, and the relative value of this book has faded as well.

An Issue That Lost Demand Over Time

Sometimes a book, relatively obscure for decades, catches the attention of collectors and soars. See Suspense Comics #3 as an example of a Golden Age book that has exploded due to attention in the Gerber Photo Journal Guides. Another example is Tales to Astonish #13, the first appearance of Groot. This is a character that greatly benefited from the Guardians of the Galaxy movies. And while the value has dropped since its peak, it is still dramatically more valuable than before the movies.

Obscure Issues That Rose to Prominence

Movie appearances, of course, are not always a predictor of long-term success for a character’s or team’s first appearance. Many comics exploded in price on the rumour of a movie, only to crash back down after box office disappointment, like Eternals #1.

A Flash in the Pan

Rarity

Let’s move to the second fundamental factor and my favourite topic: rarity. Recall that I mentioned the first appearances of three superstar characters: Batman, the Hulk, and Deadpool. For the sake of argument, let’s say they drum up similar collector energy. However, in the same Fine condition, Batman costs about 35 times more than Hulk #1, and Hulk #1 costs 175 times more than New Mutants #98. Why? Rarity.

Detective Comics #27 is likely to have around 100 copies in existence. Hulk #1 about 5,000 copies. New Mutants #98? 100,000-plus. The “supply” side differs dramatically, and it affects price accordingly.

Rarity Affects Price

You may wonder why some books are much rarer than others. Two key concepts: print run and attrition.

Some Comic Issues Had Low Print Runs

The maximum number of surviving copies, of course, can be no bigger than the number originally printed. Some comics had relatively small print runs. The first printing of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles #1 is a good example. According to Heritage Auctions, the first printing included only 3,000 copies.

What may surprise people is the significant role attrition played in the early days of comic books. For example, Marvel Comics #1 had nearly 1,000,000 copies printed in 1939, but only about 100 are thought to survive. That’s a 99.99% attrition rate. In other words, for every 10,000 printed, only about 1 survives today.

Severe Attrition Made Once-Common Books Rare

The attrition rate is closely tied to history and collector behaviour. Before the mid-1960s, practically everyone viewed comics as disposable entertainment. The further back you go, the greater the likelihood that the comic was thrown out. Combine that with paper drives during World War II, and it’s no wonder that early 1940s and 1930s comics are so tricky to find.

Let me provide a VERY rough and incomplete timeline to give you a sense of rarity. CGC president Matt Nelson has estimated that CGC has likely graded between 50% and 75% of the existing copies of highly valuable books. I’m making my estimates based on his guidance. Additionally, there’s considerable variability within comic book ages. But with those caveats aside, here are some ballpark figures:

Action Comics #1—the first Golden Age book—is thought to have about 100 copies.

Showcase #4, the first Silver Age comic, is believed to have about 1,000 copies.

By 1963, you have X-Men #1, with around 10,000 copies.

Moving into the mid- to late 1960s, many issues likely exceeded 10,000.

By 1974, you’re looking at around 40,000 surviving copies of Incredible Hulk #181 (Wolverine’s first full appearance).

The Relationship Between Age and Rarity

The numbers continue to rise from there. New Mutants #98 came out in 1991—likely 100,000+ copies still in existence. The point here is that the difference in rarity across periods is logarithmic, from the 1930s to the 1990s, at least among mainstream books. Again, there’s variability, but if you’re seeking a rough heuristic, the publication date is a good start.

Some of you may be thinking: “But a ton of modern books are extremely rare.” True—but that’s often the result of manufactured scarcity—for example, a 1-in-100 variant. Publishers know collectors love rarity, so they find ways to create new, rare books.

Del’Otto 1-in-100 Variant Cover of Amazing Spider-Man #667

Additionally, error and price variants can be tough to find for more modern books. Generally, though, comics from 1970 forward—and especially from 1980 forward—are relatively easy to find.

Scarce Star Wars #1, 35-Cent Price Variant

Condition

Let’s turn our attention to the last fundamental: condition, which is graded on a 10-point scale where 10 represents a flawless book in its original state, down to 0.5, which represents a severely flawed book, typically incomplete.

Fantastic Four #1 in Low, Mid, and Ultra-High Grade

Condition can have a profound effect on a book’s value. Let’s use the King of the Silver Age as our example: Amazing Fantasy #15, the first appearance of Spider-Man. It was published in 1962 and is likely to have around 5,000–6,000 copies in existence. Demand is certainly in the nuclear category.

Let’s check out the price of this book in increments from 2.0 to 5.0. Can you see a pattern? What do you think a 6.0 would cost?

Prices of Amazing Fantasy #15 from 2.0 to 5.0

You might say this book is selling for about $9,000 per point today. You’d be forgiven for projecting a 6.0 at $54,000, a 7.0 at $63,000, and so on. But something funny happens in the higher grades—the price goes up exponentially. At the top of the mountain, a 9.6 copy sold for $3.6 million in 2021.

Prices of Amazing Fantasy #15 at Higher Grades

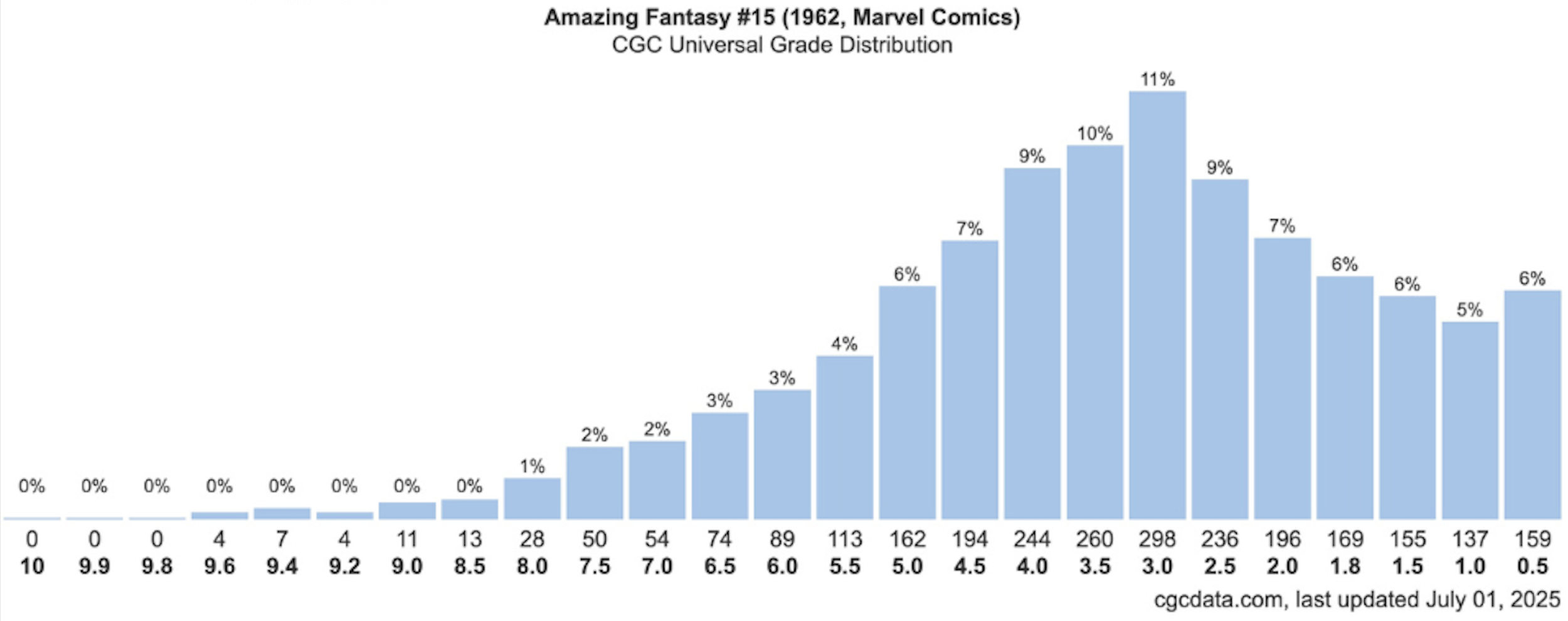

Why the acceleration in price at higher grades? To understand that, we need to look at the grade distribution of Amazing Fantasy #15.

Grade Distribution of Amazing Fantasy #15 (Universal Copies)

The distribution is much thicker toward the lower-middle range. The high-end tail starts thinning out above an 8. Why this distribution? Remember, until the mid-‘60s, almost no one considered these books collectibles. Most were read and then read again.

Let’s overlay this grade distribution with prices. The concept of supply and demand dictating price emerges once again. It makes sense that prices move up linearly in low to mid grades—people are paying for better condition, but supply is relatively consistent. However, many well-heeled collectors seek high-grade copies, where demand outstrips supply. Combine the incredible demand for AF #15 with extreme rarity at 9.6, and the price no longer seems like a mystery.

Price Overlaid on Grade Distribution – Amazing Fantasy #15

For most Golden Age and pre-1965 Silver Age comics, the overall shape of the grade distribution is similar. The price structure follows a similar pattern too—usually increasing linearly up to about a 5.5 or 6.5, then rising exponentially beyond that. A rule of thumb I’ve heard: for many Golden and Silver Age books, prices double from 6.5 to 8.0, and double again from 8.0 to 9.0—with prices accelerating even more rapidly between 9.0 and 10.

One important exception: publisher quirks. For example, EC’s publisher William Gaines kept 12 high-grade “file copies” of most EC books. As a result, the proportion of high-grade EC comics is much higher than expected compared to most comics from the late ‘40s and early ‘50s.

File Copy 4 of 12 of Crime SuspenStories #22

Be careful not to overgeneralize this grade-to-price heuristic. It works well for Golden and early Silver Age books, but not as well for more modern comics. Why? Because the grade distribution changes.

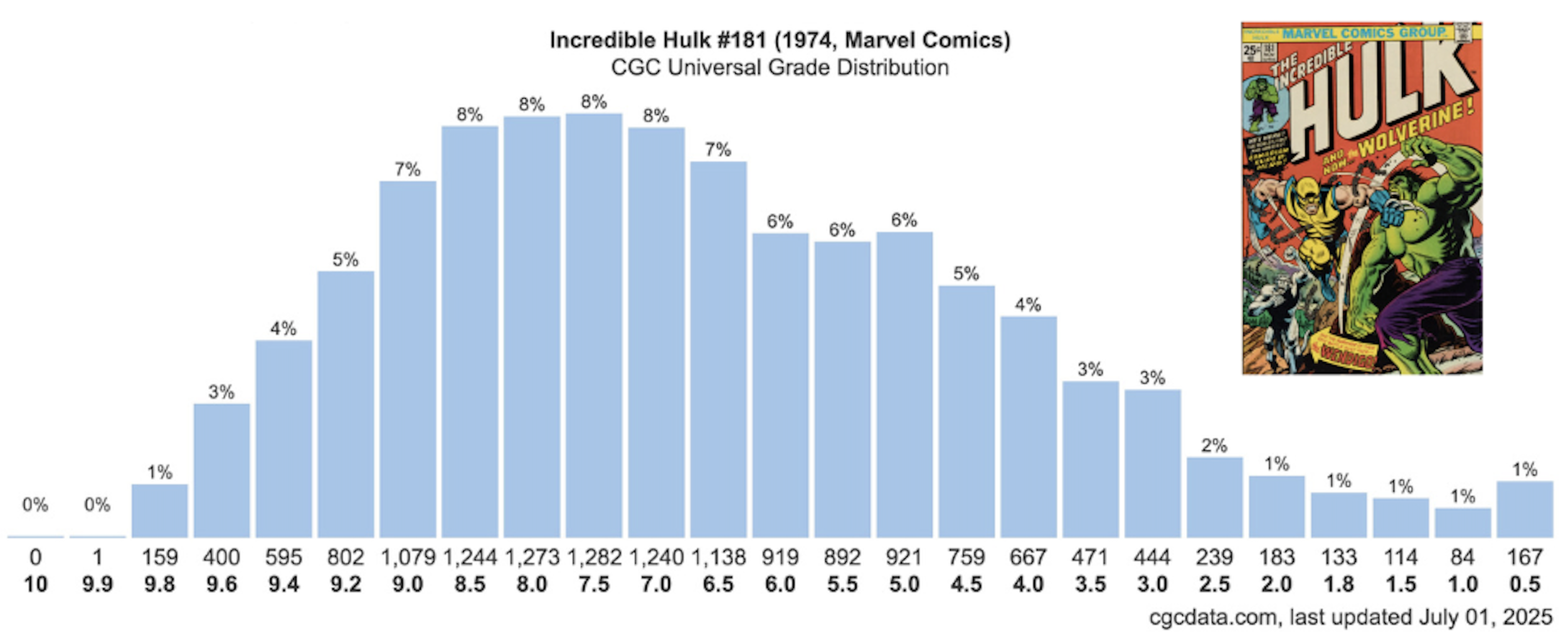

Let’s look at Hulk #181. The distribution is heaviest from about 7.0 to 8.5. It’s not until you hit 9.4 or higher that the distribution starts to thin significantly. Personally, I’d be less inclined to pay exponentially more for an 8.0 over a 6.5, given the supply.

Grade Distribution of Hulk #181

Fast forward to 1991 and check out New Mutants #98. The top end of the scale is flooded with copies. By the 1990s, readers—even kids—were handling their comics with care. Even a 9.8 is common. In fact, there are similar numbers of 9.8s of NM #98 as there are total CGC copies of AF #15 across all grades. You get the picture—modern books are not rare, and they’re not rare in high grade either.

Grade Distribution of New Mutants #98

That being said, if you were to look at 9.9s, then New Mutants #98 becomes tough to acquire. 9.9s and 10s are seldom awarded to comics of any age. They are virtually non-existent for books from the 1960s and earlier.

Estimating FMV: Putting the Fundamentals to Work

At this point, you may be thinking: “Okay—I understand how desirability, rarity, and condition relate to price. But you promised I’d learn how to estimate actual value.”

Let’s get into it.

GPAnalysis

While you can gather up-to-date price estimates from sold listings on eBay or past auctions via platforms like Heritage, my go-to resource for over a decade has been GPAnalysis. It aggregates data from eBay, auction houses, and major dealers, making it one of the most reliable tools for pricing.

Easy-to-Value Books

Popular, high-volume books are the easiest to value. They’re widely collected, frequently submitted to CGC, and regularly bought and sold—so comparables are plentiful.

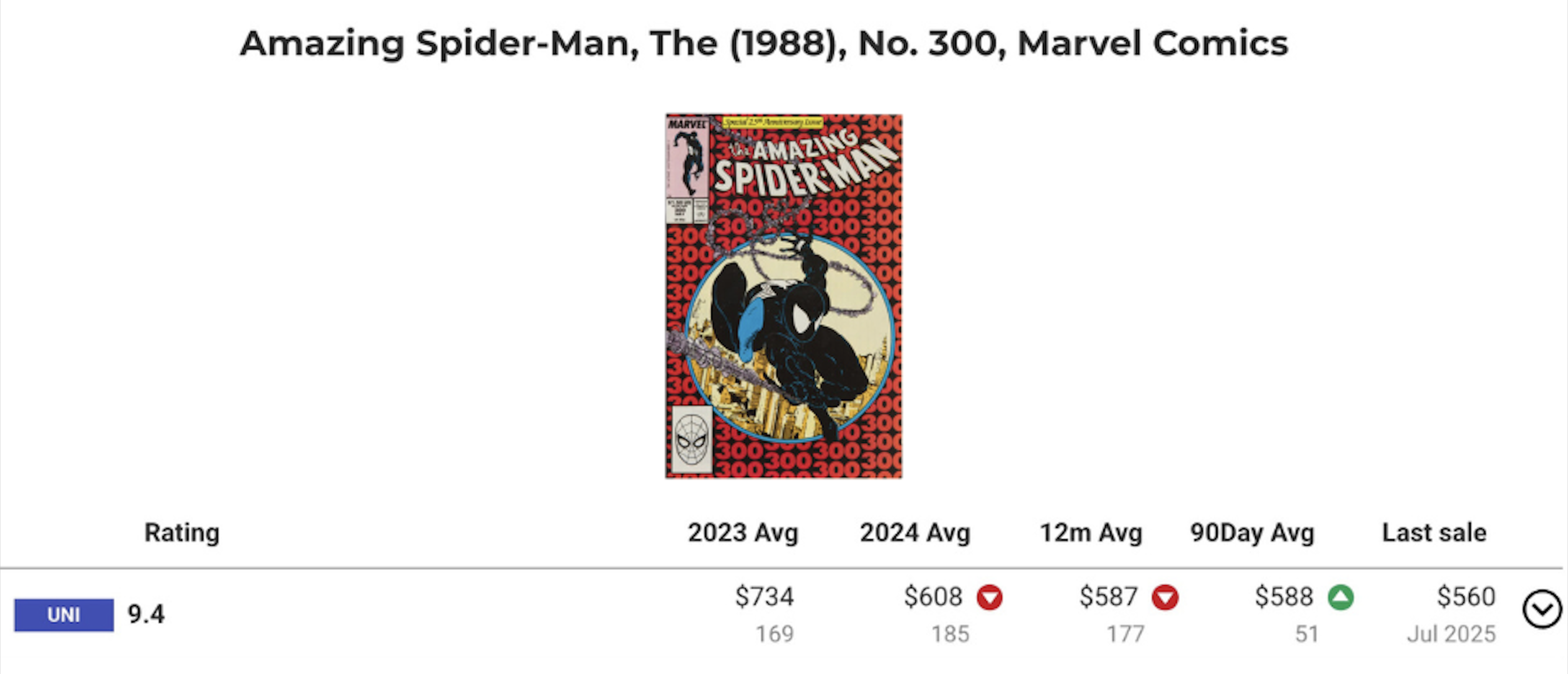

Take Amazing Spider-Man #300, the first appearance of Venom. It’s the most graded book in CGC history. Let’s say we’re interested in a 9.4 Direct Edition. GPAnalysis shows 51 recorded sales in the last 90 days with an average price of $588.

You can also view averages by year—the last 12 months, 2024, 2023—so it’s easy to feel confident that $588 reflects a fair market value (FMV) for the moment. If you're patient and vigilant across platforms, you might find it for 10% less. If you’re impulsive or in a hurry, expect to pay a higher price.

Amazing Spider-Man #300 Price Estimate for a 9.4

Mid-Level Difficulty: Silver Age Keys

Many Silver Age Marvel keys fall into what I’d call mid-level difficulty. You’ll usually find recent sales for most grades, but the data is less frequent and more volatile.

Let’s stay with Spider-Man but go back 25 years earlier to Amazing Spider-Man #1—the first issue of the legendary series and Spidey’s second overall appearance. Rather than dozens of sales per grade, you might see only a few in the last 90 days.

That means buyers must tread carefully—the fewer the sales, the more unstable the estimate. And this is where many collectors go wrong. But with a strong grasp of the fundamentals, they can make much better decisions.

Suppose I’m looking at a 2.5 copy of ASM #1. GPAnalysis reports three sales in the last 90 days, averaging $7,615, with the most recent sale at $8,599. A less experienced collector might take $7,615 as FMV and bid accordingly. That would be a mistake.

Amazing Spider-Man #1 Price Estimate for a 2.5

A more seasoned collector will zoom out and look across neighbouring grades. GPAnalysis shows that 3.0 and 3.5 copies have 90-day averages below 2.5, which doesn’t make sense. This suggests the 2.5 is mispriced.

Considering the full picture, buyers appear to be spending around $2,100–$2,500 per grade point for ASM #1 in the 2.0 to 5.0 range. That would place a reasonable FMV for a 2.5 somewhere between $5,250 and $6,250.

Amazing Spider-Man #1 Price Estimate for a 2.5 in Context

It’s also worth noting: Collectors are paying more per point for the lowest grades than they did a decade ago. For example, .5s, 1.0s, and 1.5s are commanding much more than $2,500 per point today. That seems odd to me. Do what you will with that insight.

Amazing Spider-Man #1, Per Point, Is More Expensive in Low Grades

The Most Difficult Books: Truly Rare Comics

Now let’s look at the hardest group to value: truly rare books. Here, data is often sparse or nonexistent across most grades.

Take All-American Comics #16—the first appearance of Golden Age Green Lantern. It’s tough to find, even relative to other Golden Age books. On GPAnalysis, there’s just one Universal sale in the past year: a 1.0 copy sold for $66,000.

What happens if a 3.0 Universal copy hits the market? You could multiply that $66,000 by three and guess $198,000—but that’s a wild extrapolation from a single data point.

In 2020, three sales were recorded at different grades, with price-per-point estimates ranging from $15,000 to $30,000.

Pricing Data for a Rare Comic Book

For books like this, FMV estimation becomes as much art as science. You’ll need to consider other high-end Golden Age books—have they doubled, tripled, or quadrupled in price since 2020? That may help validate or challenge your assumption.

Also ask:

Has demand for this character or title grown?

Do trusted collectors or dealers have insight?

Are there private sales you’ve heard about that aren’t publicly reported?

In these cases, you’ll have to lean back into the fundamentals and gather whatever scraps of information you can. This is why I encourage collectors to gain experience before diving into truly rare material.

Other Factors to Consider

There’s a saying you’ve probably heard: “Buy the book, not the grade.”

I get the spirit—it means that sometimes a 3.0 might appeal more than a 6.0, due to things like centring, gloss, or colour strike. But that advice isn’t very helpful for estimating FMV.

So here’s how I’d reframe it:

Estimate the price by considering the issue and grade, then adjust it up or down based on eye appeal and other factors.

For instance, comics from Fiction House can vary significantly in value depending on the colour strike. I might pay 25% more for a 3.0 with exceptional colour and 25% less for one with dull presentation. That’s an extreme case. In other examples, buyers may adjust slightly for factors such as page quality—White vs. Cream to Off-White.

Eye Appeal Can Affect Pricing Too

Two Final Pieces of Advice

As I’ve gotten more reps under my belt, two principles have consistently served me well:

If something bugs you about a book, don’t buy it.

As a good friend of mine says, that flaw will never bother you less after you buy it.If you don’t understand it, don’t buy it.

Stick to books, labels, and nuances with which you're comfortable. It's a lot like poker—if you don’t understand the situation you’re in, and others know more than you do, folding is often the best option.

I wish you the best of luck on your comic collecting journey, and I hope this guide helped you in some way.

Acknowledgements and Thanks

Images of comic books from Heritage Auctions (HA.com)

Price estimates from GPAnalysis

CGC Census numbers from CGC

Grade distribution data from CGCdata.com with permission from Greg Holland