Inked Realms 003: Worlds That Breathe

Worlds don’t just contain stories — they generate them. A truly immersive setting can launch entire universes, transforming a straightforward narrative into a mythology. Think Star Wars: what began as one film spiralled into planets, cultures, and histories that fans still explore decades later. Comics have always had this power. Their pages hold cities that feel lived-in, landscapes that shape destiny, and universes so large they can barely be contained in panels.

World-building in comics is more than a backdrop. It’s a process of giving the page weight, texture, and memory. Done right, the world isn’t just where the story happens — it is the story.

Inked Realms series:

Part One: Inked Realms 001: Lines That Speak

Part Two: Inked Realms 002: Rhythms on the Page

Part Three: Inked Realms 003: Worlds That Breathe

The Architecture of Immersion

World-building in comics faces unique constraints. Pages are static. Panels are finite. Yet within those limitations, writers and artists create depth that readers believe in.

Layers of History: A city skyline isn’t just a silhouette — it’s architecture with scars, graffiti, and evolving landmarks. Readers feel that time has passed.

Atmosphere as Character: Fog rolling over Gotham, neon lighting Mega-City One, or silence in The Dreaming — each choice tells us what kind of place this is.

Worlds Spawn Universes: A well-built city or realm doesn’t just hold a single tale. It spawns spin-offs, sequels, and legacies. One world becomes many stories.

Reader Immersion: Fans return not just for characters, but for the space itself — the familiar streets of New York in Spider-Man, or the otherworldly designs of Kirby’s Fourth World.

World-building is a kind of promise: if you step inside, there will always be more to discover.

The Creative Lens

Writers and artists collaborate to bring settings to life. The craft often unfolds through:

Detail vs. Abstraction: Some worlds overwhelm with density (Alan Moore’s Watchmen), while others invite drifting imagination (Moebius’s Incal).

Continuity: Locations that evolve give a sense of life (Gotham across decades of Batman stories).

Integration with Plot: The environment drives the story. Mega-City One isn’t just a city — it creates Judge Dredd’s cases.

Thematic Echo: Worlds Reflect Their Stories. The Dreaming is surreal and shifting because its stories are about myth and dream.

Collaboration: Often the writer scripts space loosely, while the artist fills it with texture — turning a “city street” into an entire ecosystem of signs, shadows, and lives.

Worlds succeed when they feel inevitable — when the characters could only exist there.

Masters of World-Building

Some writers transformed how comics sound and feel. They didn't just add words to art — they built rhythm through dialogue, narration, and silence.

Frank Miller: Noir Cities, Living Shadows

Miller’s gift wasn’t just writing heroes — it was reshaping the places they inhabited. Gotham in The Dark Knight Returns became a fever dream of urban collapse, a place where architecture itself weighed heavily on its aging Batman. But Miller’s purest world-building achievement was Sin City.

Sin City is a world where shadow and light are more real than brick and stone. Chiaroscuro itself is the geography. Every alley, bar, and gutter hums with menace. Miller stripped his city down to moral absolutes — black and white, innocence and corruption — and let the contradictions breed life. It isn’t just setting; it’s atmosphere made flesh.

Shadows That Live

Top 5 issues showcasing Miller’s world-building in Sin City:

The Hard Goodbye (1991) – The debut: Basin City emerges in harsh blacks and whites, violent yet mythic.

A Dame to Kill For (1993–94) – Expands the city’s underworld politics and femme fatale archetypes.

That Yellow Bastard (1996) – Corruption of power embodied in both villain and city.

Family Values (1997) – A glimpse of loyalty and betrayal in the city’s shifting undercurrents.

Hell and Back (1999–2000) – The city as predator, consuming those who dream of escape.

Chris Claremont: The Mutant Nation

Claremont’s run on X-Men didn’t just tell superhero adventures — it created an entire society. Over the course of 16 years, he transformed mutants into more than just characters; they became a metaphorical people with culture, history, politics, and generational trauma.

He built schools that felt like homes, nations like Genosha that felt terrifyingly plausible, and even alien empires like the Shi’ar that gave mutants a cosmic stage. Claremont’s genius was serialisation — layering subplot upon subplot until the X-Men world felt infinite, never static.

Worlds of Mutation

Top 5 arcs/issues showing Claremont’s mutant world-building:

Uncanny X-Men #129–137 (The Dark Phoenix Saga) – Cosmic tragedy embedded in human drama.

Uncanny X-Men #141–142 (Days of Future Past) – A dystopian future that expanded mutant lore into legacy.

Uncanny X-Men #150 – Magneto as political visionary, turning ideology into world-shaping force.

Uncanny X-Men #235–238 (Genosha) – A full mutant nation built on slavery and exploitation.

Uncanny X-Men #268 – Global espionage and mutant politics meet in layered world-spanning stakes.

Katsuhiro Otomo: Neo-Tokyo’s Ruins

Otomo’s Akira is one of the most iconic acts of world-building in comics. His Neo-Tokyo is a character in itself — sprawling, broken, teeming with life and tension. Every crumbling skyscraper, every crowded alley, is rendered with obsessive detail.

But what makes Otomo’s world resonate isn’t just the precision of his drafting — it’s the way Neo-Tokyo reflects power and collapse. Political corruption, youth rebellion, psychic apocalypse — all are mapped onto the city itself. It’s both futuristic and frighteningly real, a mirror of post-war anxieties and the fragility of modern civilisation.

Cities That Break and Burn

Top 5 moments from Akira showcasing Otomo’s world-building:

Akira Vol. 1 – Introduces the anarchic sprawl of Neo-Tokyo post-catastrophe.

Akira Vol. 2 – Political corruption and gang culture intertwine with science-fiction menace.

Akira Vol. 3 – The city fractures under psychic power, with the streets themselves becoming war zones.

Akira Vol. 4 – Rebuilding amidst chaos: humans vs. superhumans in ruined infrastructure.

Akira Vol. 6 – A finale where Neo-Tokyo itself is consumed, reborn, and mythologised.

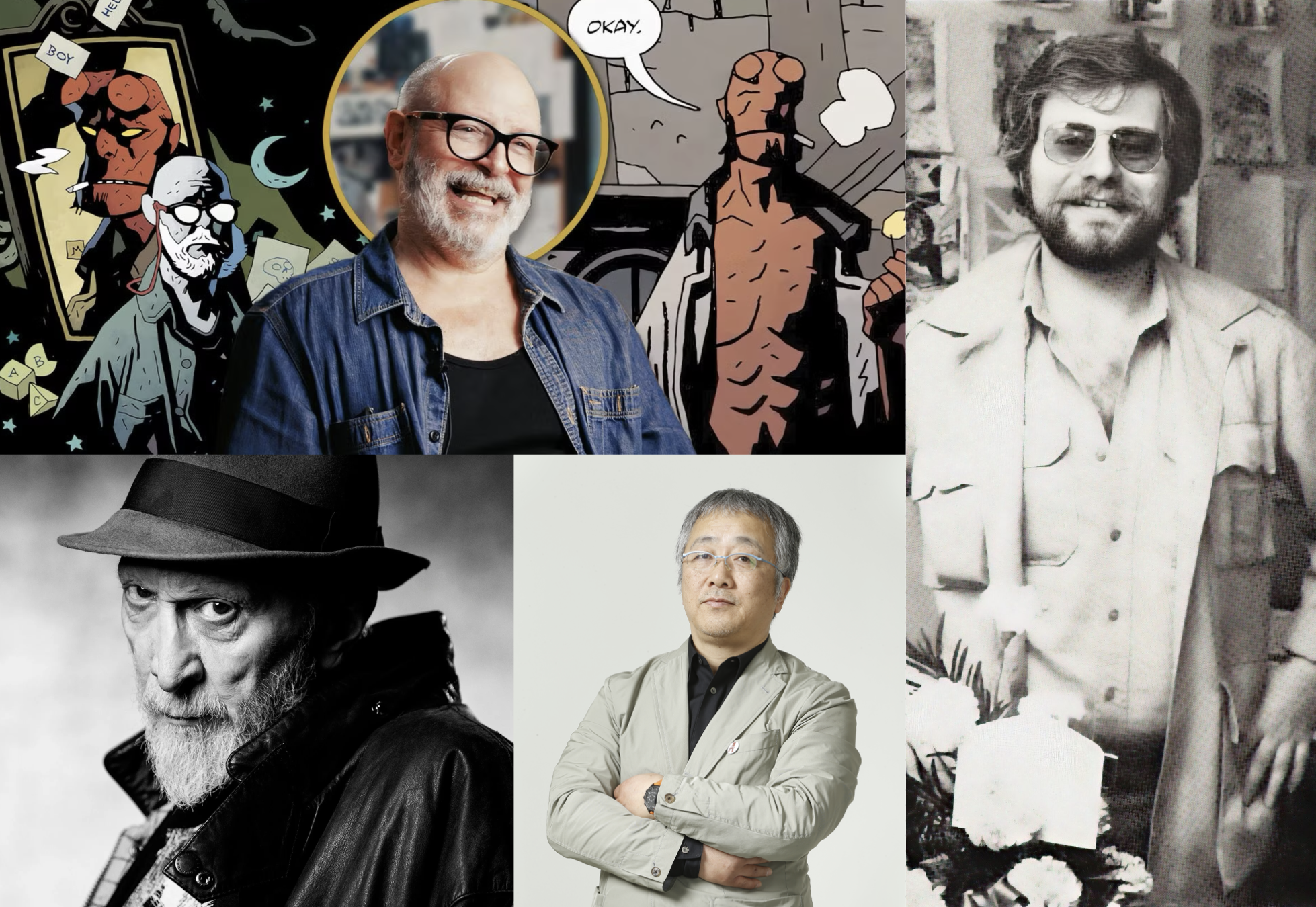

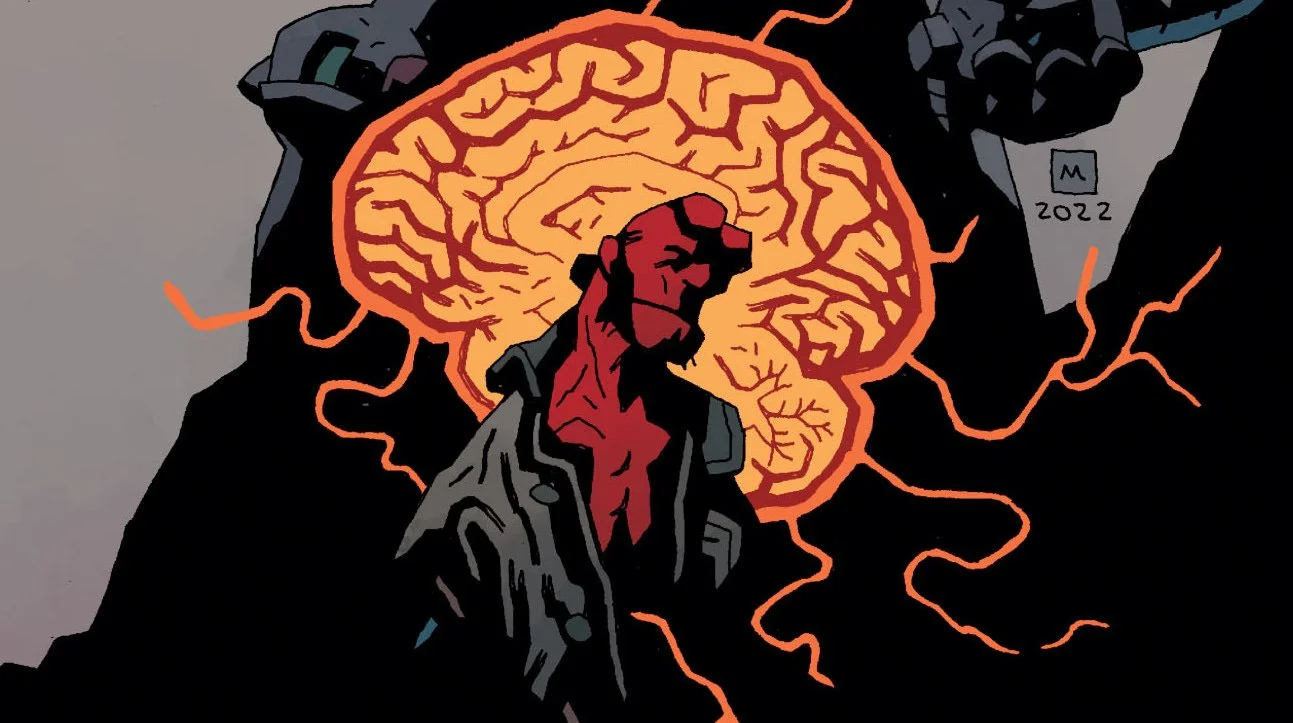

Mike Mignola: Folklore Made Flesh

Mignola’s Hellboy isn’t just a character — it’s an entire mythos. Drawing on folklore, Gothic horror, and pulp adventure, he wove a universe where every ruin, relic, and whispered myth feels like a doorway to another story.

Mignola’s approach to world-building is atmospheric minimalism. Sparse lines, heavy shadows, muted palettes — all working to create spaces dripping with supernatural weight. His world is alive with demons, faeries, and occult relics, yet it never feels bloated. The silences are as important as the monsters.

Occult Worlds

Top 5 arcs showcasing Mignola’s world-building:

Hellboy: Seed of Destruction (1994) – Introduces Hellboy and his folkloric underworld.

Wake the Devil (1996) – Expands the mythos into vampiric lore and gothic decay.

Conqueror Worm (2001) – Cosmic horror bleeds into pulp heroics.

The Wild Hunt (2008–09) – Taps into Arthurian myth with apocalyptic scope.

B.P.R.D.: Plague of Frogs (2004–06) – Shows how the world expands beyond Hellboy into ecosystems of horror.

Why Lore Matters

World-building isn’t one side of the equation — it’s the fusion of word and image. Visuals give us form, but it’s writing that shapes how we enter that form. Together, they converge sketches into lived-in places, backdrops into breathing worlds.

Lore and backstory: A throwaway line can hint at centuries of conflict, while a single drawing of a ruined statue makes that history tangible.

Names and language: A world’s identity lives in its vocabulary. “Sin City” isn’t just a skyline — Miller’s words make it throb with corruption, just as Otomo’s “Neo-Tokyo” speaks of rebirth and ruin.

Rules and stakes: Powers, politics, and fears take hold when visuals show the cost and scripts explain the consequences.

The magic of lore is how it marries what we see with what we imagine. A skyline alone doesn’t make Gotham; it’s the interplay of Miller’s jagged lines and his narration that makes the city pulse with menace. Mignola’s shadows are evocative, but it’s his folkloric prose that convinces us these creatures belong to ancient myth. When art and writing harmonise, the page stops being scenery and becomes a place we could almost step into.

Closing the Realms

World-building is the art of breathing life into paper. From Miller’s noir-soaked alleys to Claremont’s sprawling mutant nation, from Otomo’s ruined Neo-Tokyo to Mignola’s folkloric underworld — these are places that don’t just live on panels, but in our imaginations long after we close the book.

This brings our Inked Realms journey to its close. Across these three explorations, we’ve seen how comics speak through style, how they move with rhythm, and how they expand into worlds. Together, these elements demonstrate why comics aren’t just illustrated stories — they are living art forms, endlessly inventive, and bridge word and image in ways no other medium can.

Because if style is how comics speak, and rhythm is how they move, then world-building is how they live on.